charting a route, and a tool that doesn’t exist yet

when planning a trip reveals the tools we're still missing

I just got back from a solo backpacking trip in the Catskills—a much-needed chance to clear my head and recalibrate after leaving my last gig. It was also a shakedown for my current backpacking setup: I'd trimmed about three pounds and wanted to see how the new weight felt, test out my quilt for the first time instead of a sleeping bag, and play around with how I organized my pack for better access.

This meant paying close attention to the little things: how much water I was actually drinking, how much I needed to inflate my sleeping pad to counter the overnight temperature drops, and just generally getting a feel for how all the gear worked together. I'd put a pin in a potential desert trip because I knew I hadn't quite figured out my water strategy, so this was a good chance to get more precise about that, planning for a few dry camps.

The whole trip was this mix of practical problem-solving and reflective headspace. It was about dialing in the logistics, for sure, but also about giving myself room to think about what's next. I came back feeling surprisingly energized and, almost immediately, dove into planning this Pyrenees trek. Things moved a lot faster than I expected, and that's really what this post is about:

I’ve been preparing for a solo trek through the Pyrenees, looking for something quieter than the Tour du Mont Blanc — something high, remote, and doable in under a week. But in addition to finding the right route, I was also experimenting with how the process itself could be better. What would it look like if the right planning tool actually existed?

I knew from the start I wanted to use Perplexity to explore different trails and regional options. I also expected some parts of the process to remain manual — studying maps, checking distances, making judgment calls. But I wanted to test how far a language model could go, especially when it came to stitching the pieces together into something navigable. So I tried something I hadn’t done before: I used an agentic product, o3, to generate a GPX file based on an itinerary I found online.

That step — turning text into a working map — became a turning point in how I thought about this whole process.

Anchoring in the GR10

I focused mostly on a section of the GR10, from Cauterets to Gavarnie. I’d heard of the HRP and GR11, and was loosely curious about the HRP’s wilder reputation, but I wasn’t aiming to go fully off-trail or commit to an entire crossing. I just wanted a self-contained loop in the high country, ideally with a mix of mountain refuge and camping options.

One of the most helpful sources I found was a guided itinerary describing a route from Cauterets to Refuge des Oulettes de Gaube, into Ordesa Canyon, and across the Brèche de Roland back to Gavarnie. That structure had the right balance of immersion and access, so I used it as a base.

Generating the GPX

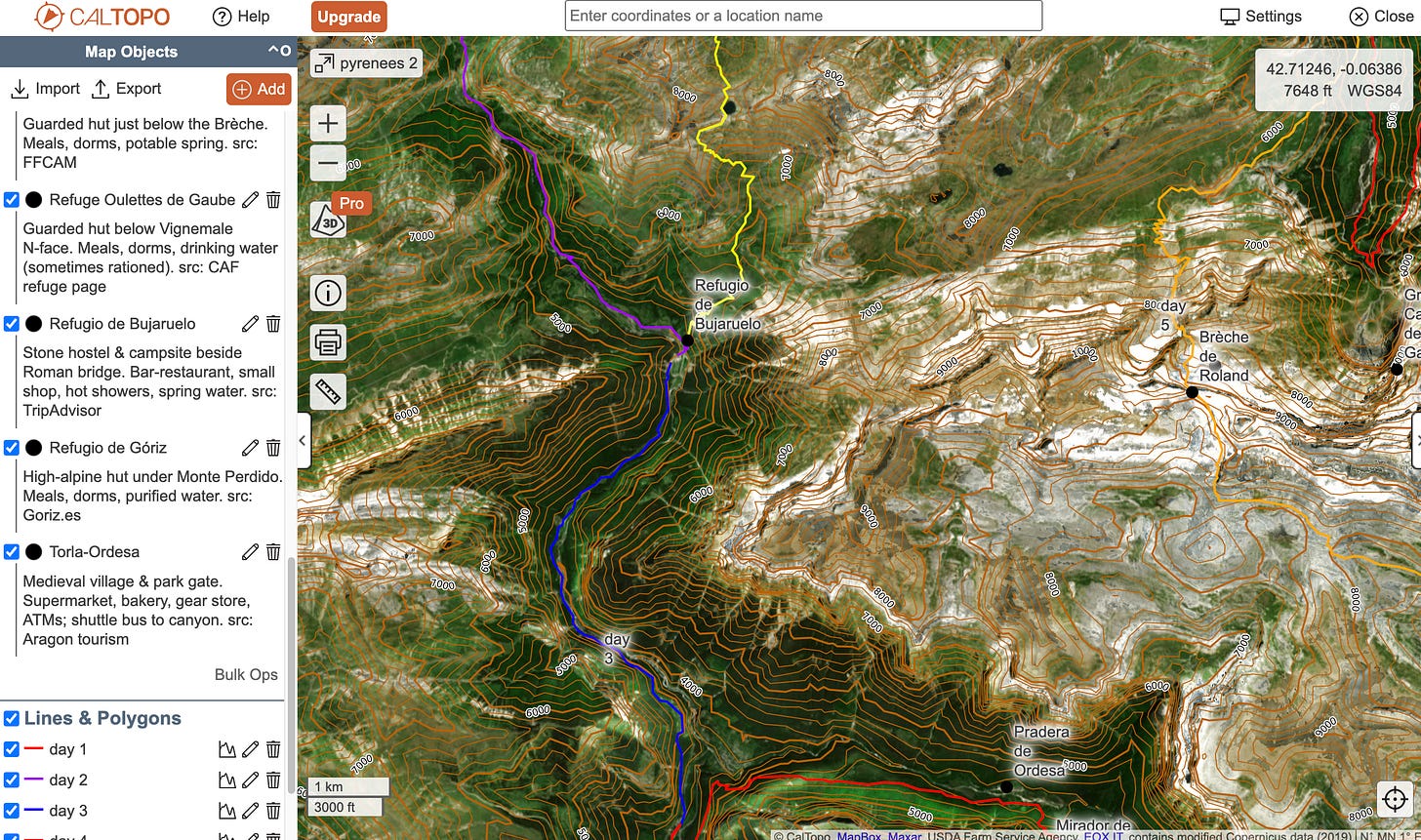

Normally, I would have built the GPX file manually from my research -- step by step, marking landmarks, likely overnights, etc. Instead, I asked the o3 model to generate a GPX from the itinerary description. It wasn’t perfect, but it was a rough version I could immediately visualize, tweak, and use to start shaping distance and elevation across days. I then imported the GPX into Caltopo to get a sense of the route. Of course, once in Caltopo, I double checked the lat/long of the waypoints to make sure they were correct.

This was one of the most surprising parts of the process. Being able to go from text to trail, without days of tab-hopping, was a glimpse of what a better planning experience could be. This allowed me to both save time and stay in flow.

Resupply, Distance, and the Feel of the Route

From there, I used Caltopo to evaluate the pacing — how far between camp options, what the elevation looked like day to day, and where resupply or food service might be available. I prefer not to carry more than three or four days of food at a time, so I shaped the route around that rhythm, topping up in towns or refuges rather than doing one big haul.

So far, I haven’t gone deep into alternate weather routes or complex bailouts. My focus has been on the feel of the route — how each day flows into the next, how much exposure and elevation is layered across the week, and where it makes sense to push or pause.

A Disjointed UX That’s Starting to Take Shape

Planning a trip like this involves a weird mix of goals, constraints, and inspirations. You’re navigating between personal thresholds (food, distance, time), incomplete or outdated information, and the challenge of actually visualizing it all in a way that makes sense.

This process showed me that the UX for this kind of planning doesn’t really exist yet. The tools are fragmented — some good at maps, some good at search, some good at generation — but none of them speak the same language. You bounce between them, making choices in isolation, and stitching things together manually.

But this also clarified something: the path toward a better tool is one step beyond combining features. The ideal tool would support the specific way people reason through these kinds of trips — how they revise goals, evaluate tradeoffs, and hold uncertainty.

For me, this was a product discovery process. And the trail I’m charting might not just be the one in the mountains.